This post is intended for an adult audience.

Background

As I’ve mentioned previously, I have long had an interest in learning about every fetish I can find. In recent years, this has partially taken the form of browsing Pixiv, delving deep into the “Related works” section, and looking through niche tags. In fact, I have a document where I collect Pixiv tags that are too obscure to have an official translation.

One of my (many) favourite tags is #アナルパール水着 (anal beads swimsuit). Since Pixiv can be difficult to navigate if you don’t have a paid account, here are links to some of my favourite examples of this genre of porn illustration:

- Melowh – Cyber Bunny Girls

- STmast – 脑洞水着 (Naoto Swimsuit) - (CW: sounding)

- (「・ω・)「♡ – 试去蹦迪的衣服 (Try on clothes for clubbing)

Inspiration

Several days ago, my girlfriend Hubris sent me a Tumblr post by spicymancer. An expansion on the anal beads swimsuit concept that adds a handcuff-based predicament.

The post has since been removed by Tumblr’s moderation, but you can still find it here on Bluesky. This drawing was inspired by an earlier artwork, uberis - Leviathans cuffkini.

After seeing this post, I couldn’t stop thinking: this wouldn’t actually be that hard to make, right? I had some free time, I had access to the required tools, and I have the body to pull off the look. I could make this fantasy into a reality.

An hour later I got started.

Making the buttplug bikini

I want to start this section by saying that I am by no means an experienced seamstress! I’ve dabbled in cosplay, repaired some clothes, and made a giant weather-resistant cushion cover, but I’m kinda in the knows-enough-to-be-dangerous category. This write-up is not intended to be a tutorial, just documentation of my own process / inspiration & tips you might consider for your own attempt. In case you are considering making your own buttplug bikini, I’m going to state the things I think should be improved up-front.

Future improvements

Hemming approach: I decided to make the garment out of a single sheet of material, and basically just use a plain hem all the way around the edge. This ended up being a huge pain, and the result looks kinda ragged. It was especially painful because of my decision to place cord inside the hem. If I made another suit like this, I’d probably choose a more common fabric-tube-turning method of sewing piping.

Software choice: I designed the pattern in Fusion 360, because I like using software that supports parametric design & geometric constraint solving. This felt like a great choice right up until it was time to print my pattern. While my pattern looked fantastic as a Fusion 360 sketch, the workflow for printing it across several sheets of A4 paper was clunky. This would’ve been a lot more bearable if I could’ve exported a drawing without needing to pay for a subscription. I should probably try to find dedicated pattern design software for my next project.

Wrong sewing machine foot: A piping foot would’ve made the sewing process so much easier. I don’t have one, so I had to make do with a zipper foot. This worked ok once I found a technique, but it was far from ideal.

Buttonholes: The process I used to sew the buttonholes was frankly terrible. I should’ve watched a tutorial about how to do this before I butchered it.

The process I followed

Now that I’ve disclaimed the flaws in my approach, here is my explanation of what I actually did.

CAD

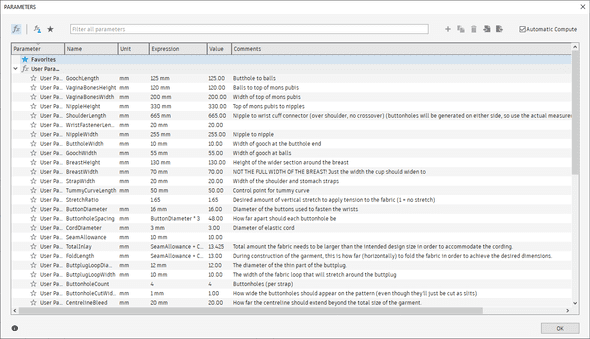

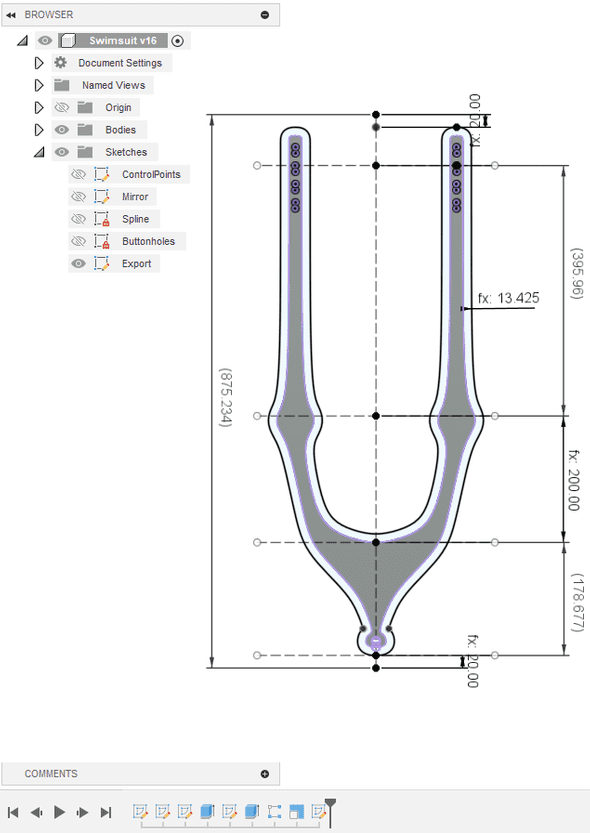

I started the process by sketching the shape of the garment in Fusion 360. My goals during this process were to make a fully-constrained sketch, and to have every dimension driven by User Parameters:

(This screenshot contains my actual measured sizes. Many people are hesitant about giving out their three measurements, but here I am giving you ten of my intimate dimensions, now say “thank you”.)

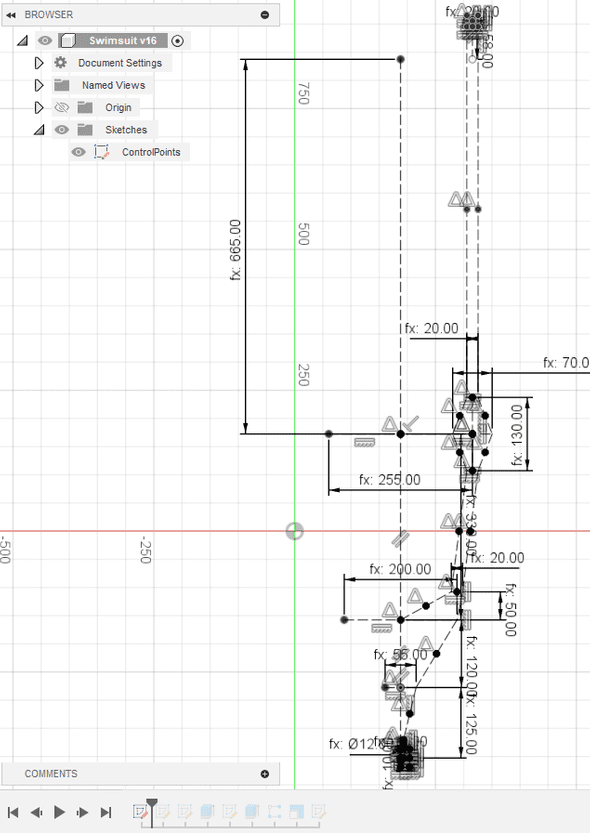

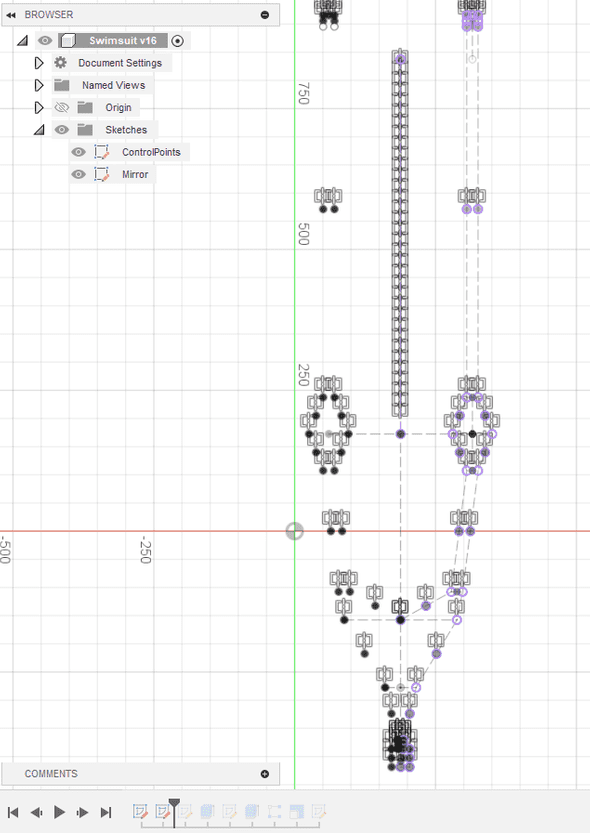

In order to keep things tidy, I used several sketches to represent different stages in the process. I used the “project geometry” feature in Fusion 360 to carry only the key sketch elements to each next stage.

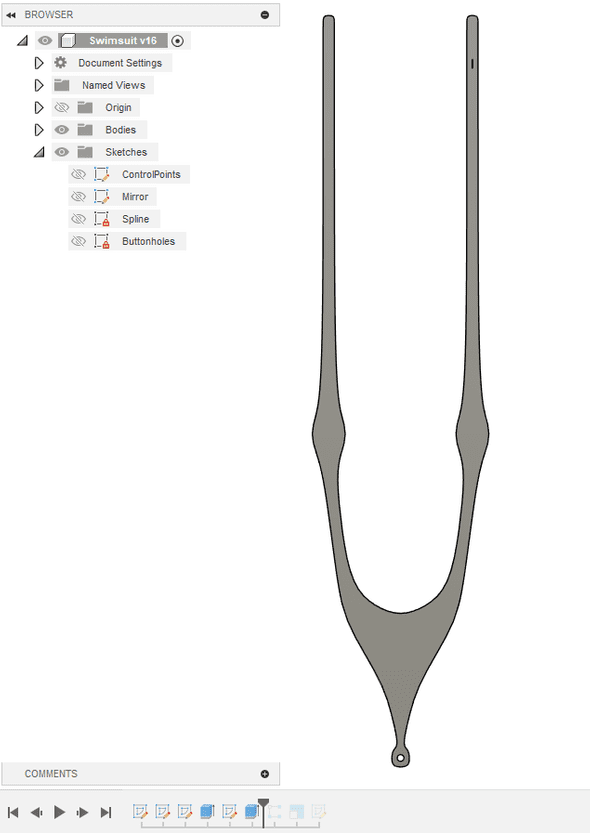

The first stage was to rough out the general layout of the swimsuit on one side, using all the measurement parameters.

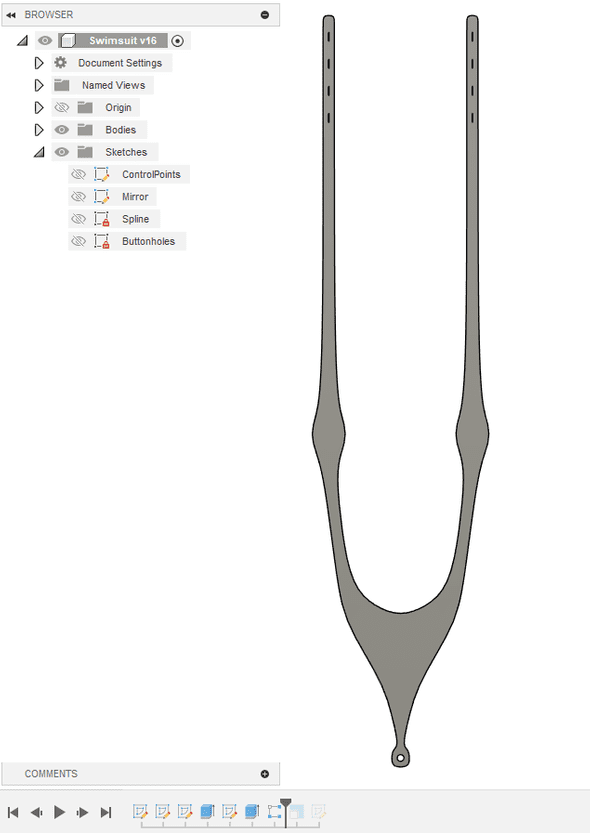

The second stage was to mirror all the key points around the centreline, since the swimsuit will be symmetrical.

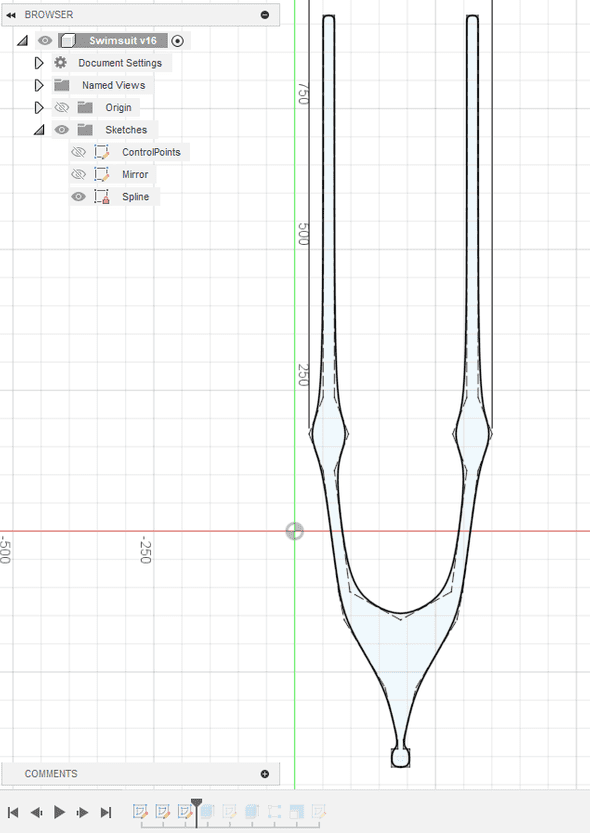

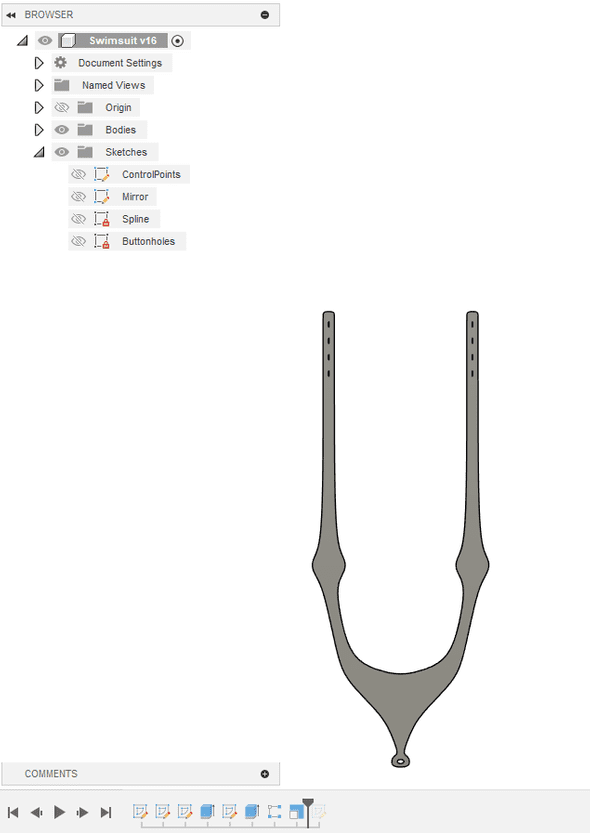

The third stage was to draw a spline using these key points, to give the swimsuit a naturalistic curved shape.

Next I extruded the sketch, added a buttonhole sketch, and cut the buttonholes out of the extrusion.

Immediately after extruding the design, I applied a pattern to the buttonhole feature to create the appropriate number of buttonholes.

This is part of the reason why I extruded the design in the previous step: I find that patterns work more reliably with parameters when they are applied to features rather than sketch geometry.

Next I added an operation to do a non-uniform rescale of the body. By shrinking the design vertically, we can compensate for the way the garment will stretch when its worn.

Finally, I created a new “measurement” sketch, which used Driven Dimensions to find the distances between key points within the design. These would be essential for correctly arranging the printed pages on the calico.

If you’d like, you can download the completed Fusion 360 design here.

Materials

With a rough idea of how much fabric I might need, it was time for the most fun part of every textiles project: spending way too much money at the fabric store. When I think of the fabric shop I tend to attribute a feeling of excitement to it, as if being surrounded by so many different materials and prints is inherently pleasurable. But I think realistically that excitement probably actually comes from the joy of having a project, and the fact that fabric purchase happens early enough in the process that I still have all my motivation.

Because thinking about it, when I inevitably have to make a second trip to the store in the final hours of the project because everything has gone to shit and I’m missing critical materials, the space feels curiously lacking of any inherent happiness.

Anyway, my shopping list this time was pretty minimal:

- Shiny pink nylon spandex fabric (I got a blend with 12% spandex)

- Thread, red to match my buttplug’s jewel (I got all-purpose thread, but if you can then I think it might be better to also get some wooly nylon for the bobbin)

- A stretch needle for my sewing machine

- Elastic cord

- Buttons for the wrist cuff connections

- Calico

Once I had the materials, I was able to fill in the remaining User Parameters. I laid the fabric flat and unstretched, grabbed two points 100mm apart, and pulled until the material achieved the desired tautness. I measured how far apart the two points now were (170mm) and this gave me the appropriate stretch ratio. (1.7)

At this point I realised I had far more spandex than I possibly needed, and if I’d measured the stretch ratio while I was still in the store I could’ve bought a lot less. I guess I’ll have to make some rave outfits, or perhaps the bodysuit from The Substance. A problem for another day.

I also plugged in the sizes of my buttons and buttplug.

Printing

Now that my sketch in Fusion 360 was finalised with all the required measurements, it was time to print it out. This is where my workflow hit a bit of a snag. It turns out the free version of Fusion 360 does not allow for exporting drawings, which means there’s not an easy way to export a 1:1 scale diagram with dimension annotations.

Fortunately the free version of Fusion 360 does allow exporting sketches as DXF files. So I right-clicked on my “Export” sketch and exported it as a DXF files.

Less fortunately, sketch exports are extremely simplistic, and do not include dimensions, points, construction lines, etc… At least they are exported at 1:1 scale though.

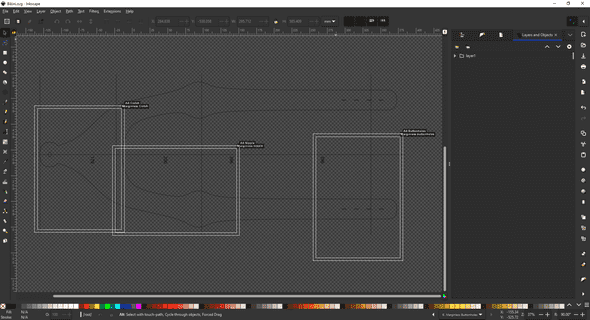

Next I imported the DXF file into Inkscape, because I think the flexibility of the new multipage feature is nice for printing large designs across multiple pages. I quickly ran into another problem though: Inkscape doesn’t have the ability to add separate guides to each page, so there’s no nice way to visualise the page margins. I ended up working around this by changing my pages from A4 to a custom page size that excluded the margin area, so that I could be sure that I was positioning my pages in a way that included all the necessary lines.

This introduced a new issue: how could I print out an smaller-than-A4 PDF onto A4 pages without rescaling the drawing. I thought this would be really easy, but after some testing I couldn’t find a way to do it on my printer. I tried a bunch of PDF tools for resizing pages, but none were able to preserve the scale. So I ended up going back to Inkscape, and adding a second set of pages that were actually A4. I then positioned these using snapping to align them centre-to-centre with the sans-margin pages. I re-ordered the pages so that these A4 pages came first so that when it came time to print the document I could easily print a custom page range of 1-3 to print only the A4 pages. With this workflow the scale was still not perfect, but it was within 1% of the intended scale, good enough for my purposes.

While I had Inkscape open, I manually added text to the page to indicate the crucial lost dimension numbers from the sketch. This would avoid me having to cross check the numbers against my computer/phone while I was assembling the pattern.

You might notice from this screenshot that my printed pages don’t cover the entire pattern. I figured that I could save paper by only printing one side of the design, since I can just flip the paper cutouts over to trace the other side. Similarly, it wasn’t necessary to print sections of the design that only consisted of straight lines, as long as I could accurately position every other part of the pattern then I could just join them up using a ruler. Hence the reference points along the centreline and the notations of distances between them.

For reference, here’s my finished Inkscape SVG file

Calico transfer

With my pattern finally printed out, I cut out the prints. I needed to make sure that my centreline reference points were still attached to the pattern pieces, so instead of cutting the whole way around the perimeter of the pattern I left little “sprue” pieces to connect the pattern pieces to their reference points. I attached these sprues to straight line segments of the pattern, so I could easily fill in the missing parts of the trace with a ruler afterwards.

Then I drew a centreline on my calico, and carefully positioned the pattern pieces along this centreline, using a ruler to position them the correct distances apart.

I used tape to hold down the pattern pieces and trace the outline, then filled in the gaps using a ruler.

Cutting

This was fairly uneventful, although the combination of stretch fabric + long edge length meant that it required a lot of pins to maintain dimensional accuracy.

Pinning & sewing

I uhhh… I don’t really want to talk about what a horrendous bodge-job I did of the pinning & sewing. I eyeballed basically everything. I eyeballed the clips & notches required in the seam allowance around the curves. I eyeballed how far to fold the hem. The elastic cord got twisted and this put weird strains on the fabric, which I hoped would stop mattering once the garment was stretched around my body. (Thankfully this hope panned out.)

It took me a while to figure out how I wanted to wrap the cord around the buttplug loop. I wanted something that would provide a strong connection, but also lie fairly flat. Here’s the approach I ended up with:

Before I started sewing, it was important to find a stitch that would yield the right balance of strength & stretch. I used several offcuts of fabric to experiment with different stitches, making sure I could still stretch the fabric to my desired stretch ratio along the stitch. A triple stretch stitch ended up being right for me, but if you’re using nylon in your bobbin then you might need a different stitch.

I used this triple stretch stitch to sew the hem around the entire outside perimeter of the garment, wrapping the cord tightly within the hem. It was very painful trying to remove the pins and hold the hem in place while feeding the fabric into the machine. Having the wrong foot on the machine did not help.

I hand-sewed around the buttplug hole, it was far too fiddly to use the machine for.

I absolutely butchered the buttonholes, I think because I cut them before I sewed around them. I wasn’t able to use my machine’s buttonhole foot, but I essentially manually sewed stretch buttonholes. I made the holes too big, so my buttons don’t fit in very satisfyingly, but once they are under tension they are secure enough. I also sewed long zigzag stitches from the seam allowance at the tips of the straps all the way down the sides of the buttonholes, in the hope of providing some extra strength for transferring the strain from the buttons into the elastic cord.

Then I just had to hand-sew the buttons on, and the project was complete!

Completion

Overall, start-to-end the process took about 16 hours of work. I completed it the day after I’d seen the post that inspired it, which is a turnaround that I’m pretty happy with.

Of course, making it is only half the story. Continue reading here for my experience wearing it.